The Lytton reaction ferry transporting a school bus across the Fraser River/via TranBC

Some welcome relief delivered late this week for the estimated for the roughly 200 people who live on the western side of the Fraser River in Lytton.

“As water levels have dropped, the Lytton ferry will be back in service as of 2:30pm this [Thursday] afternoon,” stated Ellis Junker, Operations Manager for Yellowhead Road & Bridge, the company which operates the Lytton Ferry Service. “Take care.”

The brief, two-line statement, has helped tamp down a growing level of frustration which is said to have been festering this week among ‘westside’ residents in the fallout from the Ferry’s temporary shutdown on Sunday.

Now operational, with expectations it will stay that way for the foreseeable future, its lack of service — though the catalyst — was not the ultimate source of a level of indignation in Lytton this week.

Frustrations instead centered around time frames and the divides within the community — physical and/or otherwise.

“Unfortunate” timing drives frustration

The annual melt, known as the freshet, takes place around this time of year, typically starting around mid-to-late May.

Due to previous delays with the project, it was this window of time the Village of Lytton chose to move forward with a major infrastructure project — the repair of a sewer line, which required the Village to shut down River Road.

River Road provides the only vehicle access to the eastern end of the CN Train Bridge, which becomes the lifeline for ‘westside’ residents in Lytton when the Ferry goes out of service.

What has become the custom during Ferry shutdowns is for ‘westside’ residents to be dropped off at their side of the Bridge, make the walk across, then have someone with a vehicle waiting on the other side.

via Brianna Underhill on Facebook

Without a vehicle to take them the rest of the way into Lytton, those who crossed over this week had to walk an additional kilometer before reaching steep, sandy path up the remainder of the river valley.

“I heard the story of a senior that literally had to crawl up that embankment because he was trying to get to his granddaughter’s graduation in Merritt,” said Tricia Thorpe, Lytton-area Director for the Thompson Nicola Regional District.

“You’ve got kindergarteners trying to do that…go up a sandy embankment that’s got four inches of loose sand that they’re slipping and sliding [on],” added Thorpe. “They get to school, they’re tired.”

“Those are the things that people did not expect to have happen.”

Ferry reliability undercurrent of daily life

“People are accustomed to going through part of it [the Lytton Ferry shutdown] every year,” said Thorpe. “They expect that they’re going to have to walk across that [CN] Train Bridge.”

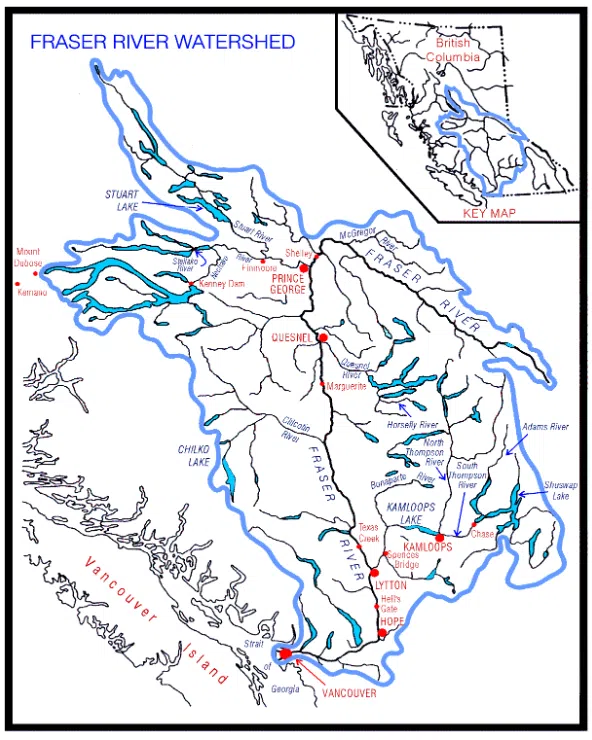

The Lytton Ferry runs across the Fraser River.

The Fraser is fed through the largest river basin in British Columbia, taking on water from sources far north of Prince George, as well as the Rockies to the east and the Coastal Mountain Range in the northwest.

As such, when the spring melt — the freshet — hits, high water levels and the debris caught up through the runoff makes it unsafe to operate the Lytton Ferry, as its reaction ferry.

Reaction ferries don’t operate using fuel or electric power.

Instead, the vessel is attached to a cable running on either side of a river and angled in a way to make the ferry act as its own rudder, allowing the river’s own power to “push” the vessel from one side to the other.

While economical and environmentally friendly, reaction ferries do have their limitations.

Fast water flows during freshet — on top of debris — runs the risk of tearing the ferry from its cables and sending it down river.

Conversely, if the water flows are too low, there won’t be enough force needed to slide the Ferry along its cable.

Because of these challenges, the operator of the Lytton Ferry, Yellowhead Road and Bridge, tries to be as proactive as possible in alerting locals of a potential shutdown, as it did in the lead up to the June 1st closure.

E-mails sent out ahead of Lytton Ferry closure June 1st/via Ellis Junker, Yellowhead Road & Bridge

After receiving the updates from the Ferry operator over the weekend while on a trip to Ottawa, Thorpe says she recognized right away the challenges that ‘westside’ residents were going to face with the combination of the shutdown and construction.

Thorpe — in emails reviewed by Radio NL — reached out directly to the Village leadership to ask that the sewer line construction be suspended until Ferry service could be restored to allow vehicle access to the Train Bridge.

While recognizing the situation as “unfortunate,” an emailed response back to Thorpe also reviewed by Radio NL noted the construction would continue on.

“It’s unfortunate that the timing is not good with the river rising,” wrote Lytton Mayor Denise O’Connor in her response to Thorpe’s appeal. “I fully recognize the challenges it brings.”

O’Connor went on to note the sewer line work is a critical piece of infrastructure that had already been undergoing delays; while also pointing out the contractor had begun the work the previous week.

“The Village was ready to begin this work in April but our hands were tied while we waited on other entities,” continued O’Connor. “The urgency of getting this sewer repair completed affects not only the Village but those on IR 17 and 18 as well.”

The email also says the Village would do everything it could to move the construction along as quickly as possible.

Communication and coordination should improve

Exterior picture of CN Train Bridge, which includes a covered walking area for pedestrians/via TranBC

The restoration of the Ferry Service on Thursday afternoon ended up being one of the shorter freshet shutdowns of the service, as spring flooding has previously shut down the service for two weeks or longer through the years.

Thorpe suggests it also came at a good time for the broader community as well.

She says as of the five-day mark Thursday, the Ferry shutdown and construction detour was creating a palpable tension at an unrelated community event in Lytton that morning — just shortly before it was announced the Ferry service was being restored that afternoon.

“They had an open house, and I got an earful from a lot of people,” said Thorpe, who says the anger was pointed in different directions.

“It’s a mixture. Some people are not pleased with the village…with the [sewer] work,” said Thorpe. “Some people think it’s a Ministry of Transport responsibility, and that they [the Ministry] can override the Village.”

Thorpe says she hopes there can be lessons drawn from the scenario.

“It’s been a learning experience for me, I’ll tell you that,” said Thorpe. “I think there just needs to be better communication overall, whether it’s between the TNRD and the Village, or whether it’s making sure that we get our messages out to the residents.”

“It’s the lack of knowledge,” she added. “I think people get upset because they don’t know what’s happening, and there wasn’t [any] advanced notice. There wasn’t any consultation [on the sewar construction] with the larger community for whatever reason. That can be really frustrating to people.”

‘Westside’ likely to remain at mercy of mother nature

While home to a sizeable percentage of those in Lytton who still call the community home — including two of the Village’s councillors — the prospect of more reliable access and egress from the ‘westside’ seems unlikely in the near future.

This may even be welcomed by some, as the region has historically been isolated.

While Indigenous tribes made the area home for centuries, in the bloody aftermath of the so-called Fraser River War of 1858 among members for the Nlaka’pamux Nation and encroaching gold miners, Indigenous settlements were destroyed and mining colonies established.

A lot of that settlement was done on the eastern, more geographically hospitable side of the Fraser, while the west side of the river became the domain of Canadian Pacific Railway as it built up its infrastructure to service mining and other interests in the region, later turning the tracks over to CN which controls the rail route today.

Once the fever of the gold rush into the Cariboo died down and British Columbia joined Confederation in 1871, the established settlements like Lytton and Lillooet would continue to draw in people, with most deciding against trying to settle on the ‘westside’ — a trend that continues even today.

The BC government estimates only around 350 people live on the west side of the Fraser River from Boston Bar to Lillooet, which makes the justification for major infrastructure spending in the area somewhat difficult.

At the same time, while the reaction ferry at Lytton does have its operational drawbacks, the province has not indicated any interest in scraping the system.

The provincial government — which did at one point oversee around 35 reaction ferries across BC — still maintains responsibility for four others aside from Lytton.

They include one which travels across the Skeena River near Terrace, the Big Bar Ferry north of Lillooet, as well as the Little Fort and McLure Ferries which cross the North Thompson River on the either side of Barriere.

While an updated ferry may not be likely for Lytton, there is an argument to be made for better maintenance of the other transportation links that are already in-place in the region, particularly as fire seasons are becoming increasingly active across the province.

A southern access and egress route to the Cog Harrington Bridge near Boston Bar remains inaccessible as alternate route, after roads leading to the span at North Bend were washed out by the 2021 atmospheric river event.

One of the challenges in getting any repairs done is the question of who is ultimately responsible for the roads.

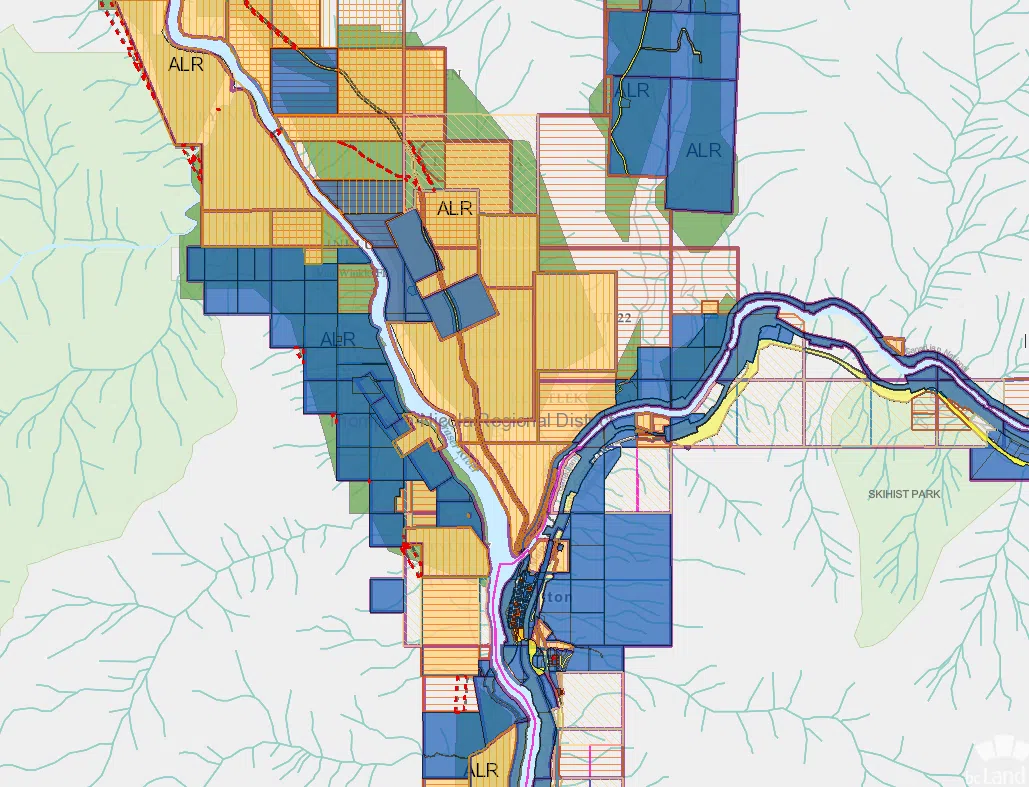

Photo showing various levels of land title and jurisdiction in the Lytton area, with each design and color representing a different land title interest/via Land Title and Survey Authority of BC

There are multiple levels of government with various levels of interest within the communities in ‘westside’ and the region as a whole, not including private firms such as mining forestry companies who are partially responsible for maintaining the roads as well.

The only other bridge out of the ‘westside’ region is to the north at Lillooet, which is also a challenge for ‘westside’ residents to access.

It requires a nearly 50-kilometer-long drive on single-lane dirt roads, some of which can include treacherous driving conditions.

But the challenges for getting out of the area also work the other way as well.

Difficulty in getting into the region has allowed much of the area, including the Lillooet Range Coastal Mountains to west of the Fraser River, to remain one of the least-disturbed areas of southern British Columbia.

The geographic area from Lillooet and Highway 99 in the north, Lillooet Lake to Harrison Lake in the West and the Fraser River on the east is home to five different Provincial Parks and three nature conservation areas.

The steep mountains and access challenges have also kept the footprint from forestry and mining operations somewhat minimal through the years.

The Nlaka’pamux Provincial Heritage Park northwest of Lytton is a favorite among British Columbia’s more seasoned outdoor adventurers.

- Nlaka’pamux Heritage Provincial Park near Lytton/via Ian Morrow on Facebook

- Petlushkwohap Mountain in the Lillooet Range to the west of Lytton/via Simon C on Facebook

- Marker commemorating opening of Cog Harrington Bridge near Boston Bar/via TranBC